Mr. Roberts is an excellent writer who explains things very clearly. It appears that good Marxist economists (certainly including Mr. Roberts) are economists first and Marxists only second. Accordingly, his writing is not diminished by meaningless, obfuscating Marxist terminology, such as surplus value, neoliberalism, or working class--words that don't appear at all.

There is no point in my summarizing Mr. Roberts' article--you can read it for yourself, and I recommend you do. Nor will I argue with him--what he says is mostly correct as far as I can see. But I do think he misses an important part of the story, and that's what I contribute here. Think of this more as an addendum than a criticism.

It is commonly noted that US productivity has declined since the 1970s. In The Great Stagnation, author Tyler Cowen suggests we've already picked technology's low-hanging fruit--electricity, the internal combustion engine, etc.--and future technological progress will be much harder to come by. Robert Gordon wrote an excellent, scholarly book explaining the same phenomenon (my review here). Peter Thiel is the most pessimistic about future growth, suggesting that AI and driverless cars, for example, are mostly just hype. (See here, and links therein.) He thinks we live in a nearly zero-growth world.

The chart below illustrates the problem, namely clearly diminished productivity growth after 1978. If this chart and the pundits above are correct, then we are in for a long stretch of slow to zero growth.

|

| (Source) |

But people are reluctant to give up hope for higher living standards, and the result is they tend to borrow more. The expectation is that times will get better soon and then they can repay the loans. But times have not gotten better and the world is deeper in debt. Growth is now further constrained by the necessary debt service, and the result is a downward spiral.

Given this background, let's use Mr. Robert's paper as a guide to see what the future holds.

He writes:

Many of the academic papers presented to the central bankers at Jackson Hole were laced with pessimism. One argued that bankers needed to coordinate monetary policy around a global ‘natural rate of interest’ for all. The problem was that “there is considerable uncertainty about where the neutral rate really lies” in each country, let alone globally. As one speaker put it: “I am cautious about using this impossible-to-measure concept to estimate the degree of policy divergence around the world (or even just the G4)”. So much for the basis of most central bank monetary policy for the last ten years.

If there is little new technology then there is little cause for new capital investment. One can't buy new computers if the new computers haven't been invented yet. The result is that the so-called "savings glut," is really an "investment drought." There are few good places to invest money. Thus it is easy to determine the natural rate of interest: it is precisely zero. At which value monetary policy has no effect at all. Corporations--never one to pass up a good deal--borrow heavily at near-zero percent interest, using the proceeds to buy back shares (a shift from equity financing to cheaper debt financing).

If monetary policy doesn't work, what about fiscal policy? Per Mr. Roberts, that's Larry Summers' suggestion. The goal, by excess government spending, is to increase aggregate demand until the economy returns to health. Governments spend all this excess cash on useless roads and bridges (Japan, China), on the military (USA; not useless, but not a productive investment), or on ever more generous entitlements (Europe, esp. southern Europe).

But more money in the back pocket doesn't necessarily increase demand. It could increase inflation, which central banks have guarded against by paying interest on reserves, thus eventually sucking back up the extra cash. While it might increase employment, in the USA (at least) that is already maxed out. And given demographic stagnation (if not decline), then there are fewer people out there to spend the money, even if you do get it into their pockets.

The result is that fiscal stimulus doesn't stimulate. We just end up with more corporate debt and more people working at low wages. Given low productivity growth, it can't be otherwise.

If monetary policy doesn't work, what about fiscal policy? Per Mr. Roberts, that's Larry Summers' suggestion. The goal, by excess government spending, is to increase aggregate demand until the economy returns to health. Governments spend all this excess cash on useless roads and bridges (Japan, China), on the military (USA; not useless, but not a productive investment), or on ever more generous entitlements (Europe, esp. southern Europe).

But more money in the back pocket doesn't necessarily increase demand. It could increase inflation, which central banks have guarded against by paying interest on reserves, thus eventually sucking back up the extra cash. While it might increase employment, in the USA (at least) that is already maxed out. And given demographic stagnation (if not decline), then there are fewer people out there to spend the money, even if you do get it into their pockets.

The result is that fiscal stimulus doesn't stimulate. We just end up with more corporate debt and more people working at low wages. Given low productivity growth, it can't be otherwise.

I mentioned above that folks are still in denial about low productivity and near zero growth. To maintain their standard of living they borrow more, unrealistically expecting to pay it back later. We've already mentioned the ways government can borrow money: by printing it or by selling treasury bonds. Otherwise known as monetary or fiscal stimulus, respectively.

In addition, folks can borrow their own money. This has certainly happened as the 2008 mortgage crisis proved. Today we have high levels of student loan, auto loan, and credit card debt.

Student loans are especially pernicious, and not just because they aren't dischargeable in bankruptcy. It's because in a near zero-growth world there are diminishing returns to education. Kids who expect to graduate into a dynamic, high-opportunity economy will be sorely disappointed when they end up as burger-flippers and dog-walkers. But absent new technology, there won't be many high-tech jobs for them to fill.

In my view, student loans are a dead-weight loss to the economy and the whole program should simply be abolished. Beyond which they destroy many people's lives.

Marxists think this is all a crisis. Mr. Roberts doesn't say that explicitly, but he seems to imply it. It could be a crisis. If, for example, central banks stop paying interest on reserves, then hyperinflation is just around the corner. In the United States that would be a civilization-ending event. I'm not predicting it, but for those who want to lie awake at night worrying about stuff, it surely is a much more likely life-ending outcome than catastrophic global warming.

Near zero growth is really bad news. It means that the next generation will not be richer than the current generation. It is stagnation, which is the opposite of a crisis. Indeed, nothing here even predicts a recession--merely steady as she goes. (It doesn't preclude one, either.)

Mr. Roberts does give us one piece of good news. He points out that in recent years profits, as a percent of gdp, have been declining.

In addition, folks can borrow their own money. This has certainly happened as the 2008 mortgage crisis proved. Today we have high levels of student loan, auto loan, and credit card debt.

Student loans are especially pernicious, and not just because they aren't dischargeable in bankruptcy. It's because in a near zero-growth world there are diminishing returns to education. Kids who expect to graduate into a dynamic, high-opportunity economy will be sorely disappointed when they end up as burger-flippers and dog-walkers. But absent new technology, there won't be many high-tech jobs for them to fill.

In my view, student loans are a dead-weight loss to the economy and the whole program should simply be abolished. Beyond which they destroy many people's lives.

Marxists think this is all a crisis. Mr. Roberts doesn't say that explicitly, but he seems to imply it. It could be a crisis. If, for example, central banks stop paying interest on reserves, then hyperinflation is just around the corner. In the United States that would be a civilization-ending event. I'm not predicting it, but for those who want to lie awake at night worrying about stuff, it surely is a much more likely life-ending outcome than catastrophic global warming.

Near zero growth is really bad news. It means that the next generation will not be richer than the current generation. It is stagnation, which is the opposite of a crisis. Indeed, nothing here even predicts a recession--merely steady as she goes. (It doesn't preclude one, either.)

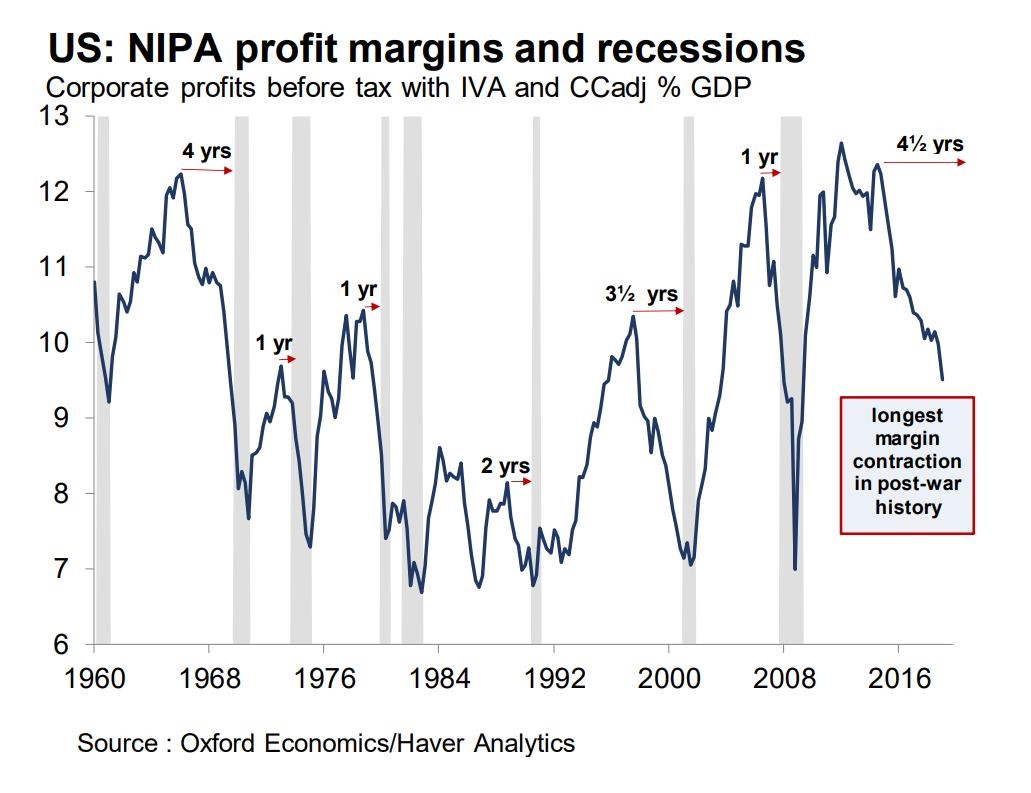

Mr. Roberts does give us one piece of good news. He points out that in recent years profits, as a percent of gdp, have been declining.

|

| (Source: https://thenextrecession.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/pear-2.jpg) |

If the returns to capital as a fraction of gdp are declining, that means the returns to labor are increasing! Even I can't see why that is a bad thing. It contradicts the claim of Thomas Piketty, who argues that capital will always get an ever larger share.

Take your good news while you can. The world is going to be increasingly short of it.

Further Reading:

No comments:

Post a Comment